This article originally premiered in Sonicscoop by David Weiss on September 18, 2017. Click here for original article.

Neal H Pogue is NOT the General Motors of mixing.

Even though we’re talking about a GRAMMY award winning mixer who’s made his mark across multiple genres, this LA-based maestro isn’t up for just anything. The project has got to turn him on, and once it does watch out, because originality is sure to ensue.

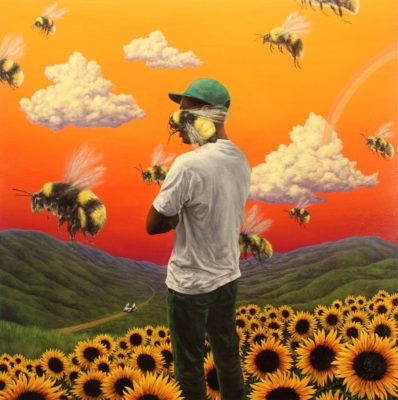

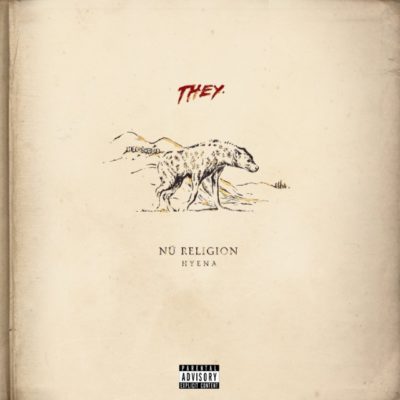

It’s a mindset that was just proven out once again with the adventurous rapper Tyler the Creator, whose brainy rhymes took his summer 2017 release, Flower Boy, to a #2 debut on the Billboard charts. The skills that he employs have also made him the choice for artists as diverse as Common, Pink, Nelly Furtado, Stevie Wonder, TLC, Lil Wayne, D.R.A.M., THEY, Metronomy, and Janelle Monae. His fader moves on Outkast’s SpeakerBoxx/The Love Below album made the daringly different “Hey Ya!” an inescapable single, and transformed music more than a little bit in the process.

Originally an aspiring drummer, Pogue pivoted to mixing after he studied audio engineering in LA – classes that he originally took on simply so he could record his own demos. But soon afterwards he caught the attention of Michael Jackson’s brother Randy, who hired him to engineer in his own LA studio, and a successful career on the other side of the glass was off and running.

From Los Angeles to Atlanta and back, a constant for Pogue has been his mix suite, dubbed “The Purple Petting Zoo” wherever it’s set up in honor of colorful fur he uses to adorn the walls. Another constant is Pogue’s trust in his instincts over technical wizardry to execute a mix, an attitude that shows on the production side as well – he produced/mixed the impossibly funky album Uncommon Good for the Montréal artist Busty and the Bass, an exciting 10-song set that just dropped.

How does this instinctual mixer keep achieving outstanding results, even while working ITB 95% of the time? It comes from the excitement he has for his craft, the intense desire to deliver for his clients, and a firm hold on musical history.

“Who Dat Boy”, mixed by Neal H Pogue on Tyler the Creator’s album “Flower Boy”

You’ve had to break down and set up The Purple Petting Zoo a few times. What are you looking for from your room? I take it it’s so that your mixes are going to translate.

Yeah, most definitely: It’s that it translates properly. What you’re hearing is real. Getting used to, what the bottom end is truly like. If you’re hearing too much low end, that can fool you too. That can make you not add as much low end as you need to.

You’ve just got to be careful. It’s always good to test it. Test your mixes in other rooms, or on the radio, or just in different speakers. Just have to keep testing it until you lock it in.

How do you make adjustments? Do you utilize acoustic materials?

Yeah, matter of fact, I kind of lucked out with on the fur. I had bought the fur years ago, just as a look — it’s fake purple fur that I got in downtown LA, at the fashion district. Then for some reason, it worked as sound reinforcement. I was like, “Wow!” I thought that I would have to get more to kind of tighten up the sound. But, the fur did it. I was shocked. I was like, “Whoa! Okay, that’s my sound reinforcement.” It’s funny how things work out.

I’m interested in how you see your own mix style evolving. You’ve certainly worked with some interesting artists recently, including Tyler the Creator. How has your style been evolving as a mixer over the last few years?

I’m still trying to figure that out, what my particular sound is. Funny, because I know my colleagues’ sounds that are in the business. But I’m not really sure what mine is yet. I work on so many different genres that I don’t know that I give myself a chance to really have a specific sound. If I do, I guess I haven’t taken the time over the last 28 years to really figure out what that is. I don’t know if that’s good or bad!

To sit there and analyze your own sound, I think you’re putting too much time into that if a person’s analyzing what their sound is. Or, if they’re known for a certain delay or reverb sound or something like that, OK — if they know that they use a particular process. It isn’t our job to really analyze our own sound. If we do then we’re focusing on the wrong thing. I think it’s more of a reactive thing. It’s more of an instinct, really. Just to be on go.

I really look at mixing as going on stage every time. I get the butterflies. I get the stage fright. At the beginning of setting up a mix, you’re like, “Okay, can I conquer this song?” or, “Can I do it justice? Can I satisfy the client? Can I step up to the plate?” That’s how I look at mixing.

Is there a common element then, or a common thread, among people who come to Neal H Pogue for a mix?

I’ve heard people say that they love how I mix vocals. I’ve heard people say that they love how I treat the drums. I’ve heard them say that they love how I treat the low end. I’ve heard so many things, and I think it’s because I work on so many different types of artists. I work on a few genres at a time. I guess my approach can be different at different stages.

When you look at those artists, the people who’ve come to you, do you see something in common among them, about who they are as artists? Is there something about all of them that maybe is in common? About the way they approach music?

No, it’s not even a common thread, which is such a beautiful thing. That a person can come to me and not have the same sound as the previous artist. I feel blessed that they see something different in me every time. Or, they see my particular sound on their song.

I feel good that that the same R&B type of artist, or the same type of hip hop artists, or the same type of pop artists, is not coming to me. Because after a while, I would feel like General Motors. And I don’t want to feel that way.

I’m a person that doesn’t like to be inside of a box, because I was raised on all types of music. I love all different types of music. I’m all over the place when it comes to just listening. That’s how I’d like to approach my mixing and my production as well, is to be all over the place.

Some people reading this are going to say, “How do I get diversified like that?” Is that something that an emerging mixer can do? Can you consciously steer your career into a diversified direction like you have?

I don’t know. In some way, you have to have natural talent for it. Some things are not just learned. I hope I’m not insulting anybody by saying this, but you just have to have the instincts. You just have to really really know. You have to have that feeling.

I guess I’ll put it this way. I would sit in my room as a kid, with my headphones on and not knowing that I was pretty much teaching myself how to listen to music. I didn’t know that this was something that I was forming. It just happened.

I would hear how the guitar, like one guitar was on one side, and one guitar is on the other side. And they’re doing different rhythms. And how they’re leveled, and how I hear this reverb, or like a delay go across my ears, certain things. I didn’t know what mixing was, but I was listening to how songs were formed. How they were arranged. How things were panned. Not knowing what the word panning is. I would hear these things in my ears. When I got to mixing, I was like, “Oh!” I applied that listening to how to mix.

Some mixers mix (from the perspective of) looking at the audience. Me, I mix looking at the band. That means, if I’m looking at the band, then that means that the drummers high hat is on the right side, not on the left side. The band is looking at me, not looking out. Because, that’s how I listen to music. I’m looking at the band. Some people mix going out towards the audience. To me that’s kind of odd. I’m the listener, so I’m going to mix it in that way. I’m going to apply it and me looking at the band. Not me being in the band looking out.

If you listen to most of my music, you’ll hear the hat on the right side, because that’s how I’m looking at the band. It’s looking at me. That’s an old school style of mixing too — that’s how guys used to mix back in the day.

What do you have in the Purple Petting Zoo? Are you using an analog console?

No, really, it is so simple, man. It’s just mixing inside the box — everything is inside the box. I just have a computer keyboard, my qwerty keys with my monitor and my speaker monitors. I have nothing fancy. I have no outboard gear. My summing comes from an old Kawai MX-8. It’s very simple. It’s just all about the pilot, man.

Are there plugins that you’ve gravitated to recently? That you find yourself using more?

Being that I was raised on SSL board, I always go to the SSL EQ’s first. Those are things I reach for first, because I’m looking for a certain sound. Every once in a while, I get the opportunity to mix outside this room. Just like on the Tyler album, I mixed that on an analog board. Not inside the box. That was a pleasure.

I mixed Flower Boy at Paramount Studios in Hollywood. I had a conversation with Tyler, even before we even mixed a song. I was telling him that it would be great to mix it on an analog board. It was something that I definitely wanted to do. Every once in a while, you just want to take that one project and just mix it on a board. Plus, he had the budget too. That was helpful.

The reasons why I’m mixing in the box, and I’ve been doing it for so long, is because of budgets. It’s just the budget cuts that have me inside this room, about 98% of the time. That 2% I’ll get the pleasure of working outside the room and working on the board. It always feels good.

Well it sounds like you don’t feel limited by working in the box, but when you get a chance to work on a console, that gives you something more. What are the benefits of mixing on a real desk?

Oh yeah, it’s like being at home. Being on that board and touching the faders and touching the EQ’s. Physically touching it, that’s how I would really love to mix. But, it is what it … Mixing in the box, it is a convenience. If you want to recall something, it just comes right back up.

Creating with the Creator

What else did you discuss creatively with Tyler before you started mixing Flower Boy?

Tyler is a big Outkast fan. And he’s a big nerd fan too. He just wanted it to be great, and I wanted it to be great too. Sonically, we just wanted it to be the best hip hop record. Nowadays, a lot of time isn’t put into the sonics, when it comes to hip hop. A lot of it is just on go. It’s not about really taking the time to really make sure that it really sounds great. Those are things that we’re talking about.

If you listen to the record, it’s very musical too. We wanted to really match that analog sound with the musicality. I think we did a pretty good job. People do talk about the mixes, just as much as the songs. I think that we did our job. I think it’s mission accomplished.

With that album’s first track, “Forward,” I was really taken with how that song just ebbs and flows, and how much skill I thought it took to build that mix. How do you build a mix in a song like that?

Tyler would probably hate the word “genius,” but Tyler has this thing. He has this mission of just being different. He has his own ways of approaching things. He takes pride in that too. You can hear it, how that album sounds. For my part, you have to respect the music, and you have to give it time.

When it comes to mixes, I always build from my drums first. I’m a drummer, and they say that drummers, drummers make the best producers because they’re always listening. They always know that they have to keep the groove and have to lock in. They have to make sure that everybody is following them. We’re just better listeners. I think that helped me out a lot.

But building that record, I can’t quite explain how I built the thing. Sometimes it’s just — and I keep using this word — it’s such a reactive thing. It’s hard to know how I did it and why I did it. I know that frustrates the interviewer, but it was just one of those things where, being that I’m such a music lover, and I get inside the songs, that sometimes it’s like an out-of-body experience. Somehow I built something up.

I think that’s good. No matter what a person does in their career, if people tell me that they do this thing, and they go into a zone, and then they come out and it’s done, I always love to hear that.

It’s just like blacking out. It’s literally like spiritually blacking out. And that’s how I hear it. I find that I personally get inside the music, and it just takes me.

Tyler is such a melodic person — he loves melody, he loves color. Tyler likes the type of records that I love. Things that have nothing to do with what he’s creating. He listens to all types of music. That’s what makes who he is as a creator, no pun intended. We apply that to what we’re doing at that time. All these influences that are inside of our brains, that’s what comes out.

Responding “I don’t know” to a technical question is kind of a lame answer. But, sometimes music leads you. That’s the power of music. It’s just a thing where you just go. When music talks to me, I have to answer back by EQing a certain way, and doing this and that.

Some people feel color and some people feel numbers. I feel colors when it comes to music. Everything touching me is in color. When I feel that, it makes me react in a certain way. That’s why it’s so hard to explain. Some guys are very technical about music, and all this 5K and all that, and I’m not that guy. To me, it just moves me in a certain way.

That notwithstanding, I’m going to ask about your low end management though. I heard again and again throughout this album, tracks and sounds, that I think in the wrong hands would have overwhelmed the track on the low end, like “Who Dat Boy” and also “Where This Flower Blooms,” something that was crazy and deep, but it didn’t take things over. How do you make sure deep synths and other bass sounds don’t overwhelm everything?

I will say when it comes to low end with this record, I wanted to please everybody. I wanted to please the most grungiest of people who listen to low end music. I wanted to please the people that really appreciate good music too, on a melodic level. I kind of wanted to touch everybody. When it comes to the low end, I wanted to hit the most dirtiest hip hop listener. I wanted it to have that southern low end. This is Tyler too, so I speak for Tyler as well, we just wanted it to be as dirty as possible. Then up on top as sweet as possible too.

We just wanted to be as colorful on top, but as dirty on the bottom, so it pleases the most hip hop listener and it pleases the pop, R&B, whatever listener, as well. It’s almost like creating this like rainbow children of people to just listen to this album.

For example, a lot of times he’ll have an 808, and on a song like “Who Dat Boy” we just wanted to make sure that it was just busting out of the speakers. Once you hear it, it like … It’s like your face kind of turns upside down, like you smelled something wrong. But, it’s so good. You know that face that a person makes when you hear something that sounds so good, but then you make face where you feel like you smelled some Limburger cheese or something?

That song has what I’d call “fright inducing synths.” I think its one of the scariest songs ever recorded.

Yeah, it’s like hip hop horror.

Pure Hip Hop

On the Flower Boy song “Pot Hole,” the beat starts out so spare and minimalist, but it’s so effective. Then you start getting these jazzy little snare and tom surprises along the way.

That to me was a pure hip hop song. It has such a throwback feel, feel-good song that took me back like 20 years or so.

I’m a kid who grew up on cartoons. I have a huge imagination. Not saying that this was a cartoon song, but it’s just, my brain will go back to something to a situation, or a certain group from back in the day, and I’ll lock into that sound. I don’t know what group I locked into, but just that beat alone just makes you go back to the ‘90’s. It just has that thing about it.

It was so easy to kind of lock into that, because it took you back in time. And that’s what I mean by mixing can be such a reactive thing, because it can take me to a moment at any time. It will take me back to somewhere. I’ll just lock into it, and I’ll just start doing my thing.

It sounds like you’re saying as a mixer, an important quality is to be kind of like open to yourself, as a person, and open to your own experiences. Is that right?

Yeah, and to really know the history of music. If a client says, “I want it to sound like this,” I want to know what that is. Thank God, I’ve got an encyclopedia inside my brain. Being fan of Fleetwood Mac, and Parliament-Funkadelic fan, Neil Diamond, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Joni Mitchell, ABBA fan, to being an Isley Brothers, Kenny Rogers, Talking Heads, Blondie, Black Flag fan.

I’m all over the place. I like punk, I like hip hop. Everything, it’s just in my head. As soon as I hear a song, or if a client gives me a song and it reminds me of something, then I can automatically lock into it.

So will you reference multiple genres within one song? If a song calls for punk and hip hop and pop, all at once, is it okay to go there and mix those genres up within one track?

Oh yeah. I don’t go back and try and look in iTunes and references — it’s all in my head. I’ve never referenced anything. I never go back and sit and listen to another album to get some influence. No, I never do that. It’s already in my head. At any given time, an old song will pop in my head, and I’ll start singing.

The Place of Space

I also checked out Nu Religion: Hyena, by THEY. How did you come to be working with THEY and what was the discussion you had with them before doing that song?

My manager at that time was having lunch with somebody, or having lunch with their manager, or with their label or something. I guess it was like, “Hey you should have Neal mix this record, this album.” They were like, “Cool.” It happens a lot. Somebody will say, “Hey you should have Neal do that.” Then they go, “Oh wow, I never thought of that.”

SonicScoop did an article a while ago about managers for producers and mixers. Do you feel having a manager can be beneficial to your career?

It’s very important to have a manager, because I’m just locked inside this room, almost all the time. When you have a manager that’s going to a lunch meeting, or going to an office meeting, or going to a label meeting, you just never know what will come out of there.

A person may mention something then someone else may go, “Oh, why don’t you get…” So you just never know what may happen, what comes out of a conversation. It’s definitely important to have a manager out there, fighting for you or having your back, or just naturally knowing what’s going to work.

I wanted to ask you a couple questions about Nu Religion: Hyena then. I heard interesting uses of space within that album. What are your own feelings on space — when to leave it in a song and when to fill it up?

I always talk to the kids that are coming up, and I always say, “You have to listen to the song first. Don’t just reach for the compression. Don’t just reach for a reverb, because you think that’s what people do. No, you have to do it because you feel it.”

Going back, once again, to what I said before, you let the song talk to you. Sometimes, of course, the client will say, “Okay, I want this to sound big.” So you gotta make it sound big. But I always tell people, just let the song talk to you, don’t just reach for anything, because that’s what you normally do. Reach for it, because that’s what the music calls for. That’s what it wants you to do.

When it comes to creating space itself in the mix, like acheiving separationg between tracks, I think songs that have less in it are harder to mix than songs that have a bunch of sounds in it. It’s harder to mix because you’ve got to make something out of it. At the same time, you hope that the production is good where you don’t have to “fix in the mix,” as they say. Hopefully, it’s already a good song, so you’re not trying to polish a turd and trying and make something out of it.

To me, space is all about how you pan things and how you make the song interesting. I would say, being that kids are listening on earbuds now, how can you make it interesting while they’re listening to the song inside headphones? Is it taking them on a ride? Or, is it just boring? What are they going to be listening for? You’ve got to make something for the consumer very interesting. That’s what I like to do all the time.

I try and make a mix as interesting as possible. Make the things move. Maybe something is panned to the left side, or the right side, or something to the middle of your forehead. It’s always going to be interesting enough, or I’ll use a delay to move a certain way, or in a certain time signature. It just depends on the song, but I just love to give something interesting to the listener.

Produced and Mixed by Neal H Pogue, “Common Ground” by Busty and the Bass

Fearless Mixing

Does the knowledge that a great deal of people will be listening on headphones, on earbuds, affect the way that you mix?

I always tell my clients, “Don’t check a mix on earbuds,” and they go, “Oh well, that’s what the kids are listening to.” But you should listen to a mix on speakers, because the people that are listening on earbuds, they’re not really necessarily listening for the mix first. They’re listening for the song. If the mix moves them, then that’s even better.

So I never mix with earbuds. I never mix for laptops. It’s never going to please you. If you’re looking for the low end in some laptop speakers, you’re going to be disappointed. You always listen on speakers first. I always mix for people in their cars and people in their houses. Not for earbuds. I think that’s the wrong way to do it.

That’s why, I hate to say, some mixes don’t sound as great nowadays, because people are mixing for earbuds. I call that fool’s gold.

For emerging mixers who are reading this, what would you like to express to them, so that they have some good basic career advice? What do you want them to know, so that they can take their career to the next level?

Form your sound with no fear. Of course, take from different influences, but take pride in doing your own thing and creating your own sound. Whatever that is. Don’t follow. That’s what’s going to separate you from the pack.

You asked me earlier, “What is my sound?” I don’t know what that is, but I know that I don’t sound like anybody else. I take pride in that. I come from the era where people dare not sound like another mixer. People hire you for what you do. If you sound like somebody else, then they’re just going to go back to the source.

Just like great singers, they’re a smorgasbord, like a gumbo of different influences, and that’s what I think that I am: I’m just a gumbo of different things that I’ve heard.

-

Recent Posts

- Busty and the Bass Team With George Clinton for ‘Baggy Eyed Dopeman’: Premiere

- Justin Tranter, Lucky Daye and More Attend Annual L.A. Nominees Grammy Brunch

- How GRAMMY-winning producer Neal Pogue Used Ozone 8 On Robyn’s ‘Honey’

- The Secret History of Outkast’s ‘Speakerboxxx/The Love Below:’ the Last Truly Great Double Album

- Neal H Pogue: Instinctual Mixing for Tyler the Creator